Note: I rarely annotate/cite references in my letters, but this is an exception due to the content.

☉︎ in 5° Sagittarius : ☽︎ in 0° Virgo : Anno Vvii

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.

To my Unknown Friend: Greeting and health.

I am generally loathe to bring up stories of my adolescence, though in this case, it seems like a good way to introduce the subject matter and my connection to it. During my final years in high school, I attended a rabidly conservative religious school. In my time there, the principal sat me down one day in his office and handed me a sheet of paper. It was a flyer for the Ayn Rand Institute and its scholarship essay contest to write about one of the selected topics regarding Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. I’d never heard of Ayn Rand. The goal, though, per my principal, was to shred the philosophy of Ayn Rand as godless, morally bankrupt, and most certainly antithetical to Christian values. As a voracious reader, however, I was intrigued, especially after I learned the book was about an architect. My family was full of architects and I had a fascination with the field.

I was surprised to find, after reading the book, that it aligned with many of my own internal values. Not all of them, of course, but so much of the world around me made sense suddenly. It was my first brush with what “sudden enlightenment” must feel like, though on a very small scale. I immediately snatched up Atlas Shrugged and my world was turned upside down, literally, overnight.

The problem I found was both The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged presented some deep philosophical concepts, but they were fictionalized. I had zero experience or exposure to Rand’s philosophy, so her aesthetic theory of “selective re-creation of reality according to an artist’s metaphysical value-judgments” (Rand, 1975a, p. 45) was foreign to me. I was unable to parse out much more than a basic thesis of either novel and the understanding that there had to be something more than a hatred for religion and a novel definition (so I thought at the time) of selfishness.

It was about the same time that I was reading The Fountainhead that I discovered Crowley through the works of Anton LaVey. I was in the midst of a huge shift from the values of my childhood upbringing and Crowley was just enough to push me over the edge of change—though I sometimes wonder if it was truly a change of values or merely a recognition of innate values rising to the surface.

Today’s formal education is not as expansive as it once was even 50 years ago, much less 100-200 years ago. Most, I think, don’t read for expansion of knowledge but for supporting prejudices. And the far majority that I run across (though not representative of a majority of people, certainly) tend to lack the comprehension necessary to discern knowledge from propaganda. I read Rand as an antagonist and found myself intrigued by the candor of her work. I built a collection of everything I could get my hands on, and continue to expand that over the years as more work became available. Much like Crowley’s corpus, I’ve read everything I can get my hands on to ensure I have as complete a picture as possible for me.

Which leads to a discussion that comes up regularly over the decades about the usefulness of Ayn Rand in relation to Thelema based on a couple of side comments by Crowley and others. It is alleged that one of Crowley’s disciples compared him to Howard Roark in The Fountainhead. I can’t find any reference to that anywhere, but I can see the comparison even if the anecdote is untrue. What I do have is Crowley suggesting that The Fountainhead was “a first-class book — most encouraging” (A. Crowley, personal communication to Sascha Germer, February 14, 1947).

One of the more direct recommendations comes from Marcelo Motta—and I realize that many will debate the value of his advice, but ad hominems don’t interest me in the pursuit of understanding. He claimed that “the social aspect of this verse [AL 2.59, the “Love all, lest perchance is a King concealed!” verse] has been sensed by a woman writer, Ayn Rand, and developed in two works of fiction worthy of perusal by Thelemites: The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged. Although her reasoning is often mixed-up or naive, she grasped the main point well enough” (Crowley, 1975, p. 154). Motta took the smart route, I think, in seeing the value of Rand’s work where it was important, offering a cultural reference that was relatable to the masses, and discarding that which didn’t work while even offering a warning not to take Rand too seriously on the whole.

Our society, with the advent and (im)maturation of the Internet, has become far more all-or-nothing polarized in its ability to parse useful information from any source without offering some kind commentary on the ethics, politics, religious values, or bathroom habits of an author. When it comes to Rand, the views of entertainment “news” websites and misguided and misaligned politicians take precedence in the minds of those who lack the critical skills to examine source materials without allowing bias to overly influence interpretation.

My first question, of course, is why did Motta feel so strongly about this? Decades of work with Rand’s material allows me to answer that—at least to my own satisfaction even if I will never know his own motivations for sure. My comments here will remain focused on the connection between the thoughts of Rand and Crowley while I leave the current political minefield for those that wish to debate such nonsense. Nor I will tackle many of the misunderstandings by Thelemites (and others) on issues like Rand favoring the rich over the poor (which is untrue) or that only CEOs and big businesses are special (also untrue) and that monetary wealth is the measure of which individuals are important to a society (quite untrue).

The only comment I will make in this regard is I remain surprised by liberals, in particular, who criticize Rand on many different levels while ignoring her comments that (a) make her consistent throughout her work and as an exemplar of her philosophy and (b) show an inconsistency of modern liberalism that is an embarrassment to social justice and welfare. I would submit that most of this is due to the lack of comprehension, especially in Thelemic circles, of Rand’s work in the details. Her life was no bed of roses. Her behavior did little to endear others to her. Her philosophy makes the most complicated modern Thelemic writing look like child’s play. But she’s had more influence on our society—for better and, mostly out of misunderstanding of her work by the political Right, for worse—than any Thelemite alive today.

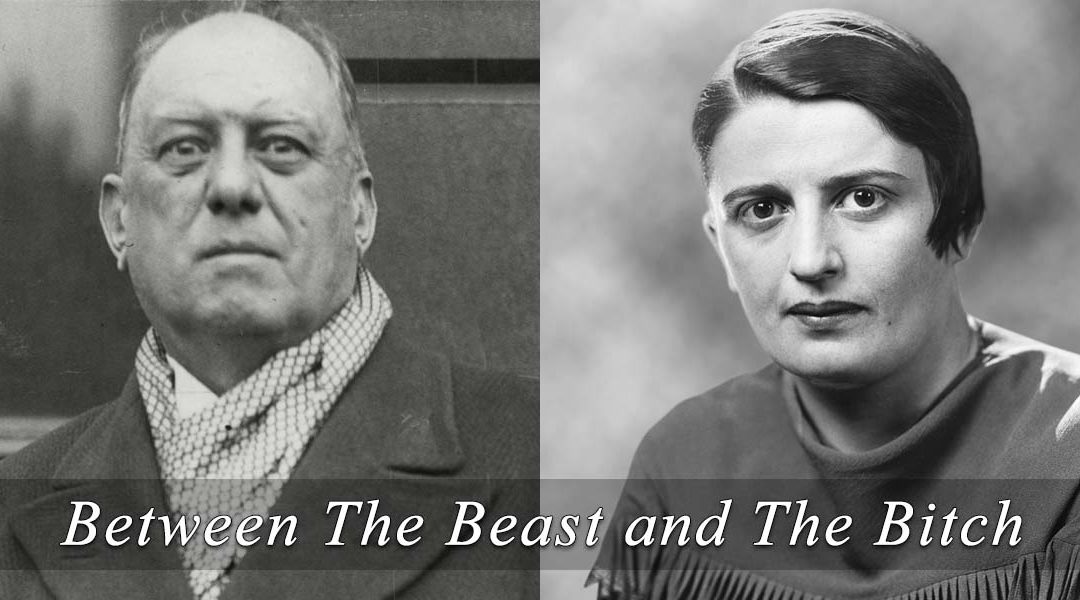

That said, we can agree that Rand was a bitch. And then move on.

Moving on, though, I start with Motta’s assertion about Rand grasping the broad strokes of Thelema’s social aspect in her works of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged. While, in my opinion, far more superficial than much of her other nonfiction work, I see where Motta is headed here. Sit down any number of Thelemites who claim to have read Rand and/or claim to hate Rand and ask them to provide the thesis of either book, and you will immediately get blank stares (and a deluge of ad hominems). Granted, I come up with a different view of theme than Rand claims for herself. I would defer to her exposition first (a form of ‘appeal to my writings,’ if you will).

Rand claimed the theme of The Fountainhead was “individualism versus collectivism, not in politics, but in man’s soul” (Rand, 1963, p. 68). For Atlas Shrugged, she said it was “The role of the mind in man’s existence” (Rand, 1975b, p. 80). These seem innocuous enough. But what is it about either book that we can take back into Thelema with us? What social sense of Thelema is found in each novel? I have asked this question regularly of Thelemites, in particular, when it comes to debates—”what is the single sentence summary of Rand’s philosophy that is expressed in her novel Atlas Shrugged?” It is not a single sentence summary of Rand’s entire philosophy but only that portion which she was attempting to express in this particular piece of fiction. It never surprises me when that question is met with silence. It is that test in which I can separate those who have read Rand and those who have pretended to read Rand. The answer is so obvious that it’s one of the most highly quoted lines out of the book itself. I’ll come back to this is a bit.

We have to keep in mind, of course, that she defined her terms specifically, if not novelly in many ways. For instance, altruism isn’t just being uber-nice to each other (as most people would define it). How did she define it? “The basic principle of altruism is that man has no right to exist for his own sake, that service to others is the only justification of his existence, and that self-sacrifice is his highest moral duty, virtue and value” (Rand, 1984b, p. 61). Or, in our own terminology, the ethics of the previous aeon. Same thing with selfishness—which, under Rand, might even be more compassionate than Christianity without the concept of self-sacrifice which Thelema rejects.

Even her definition of capitalism isn’t particularly standard, though it may be the one thing that she gets right. Rand (1967) writes

The recognition of individual rights entails the banishment of physical force from human relationships: basically, rights can be violated only by means of force. In a capitalist society, no man or group may initiate the use of physical force against others. (p. 19)

We find the use of force even in the economic sphere under America’s so-called Capitalist society. I am quite sure Rand would not approve despite the attempts to suggest this is all going according to her plan—which, ironically, this use of economic violence against individuals, citizens, and whole segments of society is precisely what Atlas Shrugged illustrates. The fact that so many liberals miss all this shows an ignorance of the actual content of Atlas Shrugged.

Arguing against Rand without using her specific terminology is foolish. So, of course, people are upset with her because she’s against altruism (as defined by her) and for selfishness (again, as defined by her). But ignoring that Rand discussed charity, saving peoples lives in emergencies, and all kinds of issues because of the word selfishness (which, in Rand’s system of thought, would include charity, saving people’s lives, and cooperation between people) is just outright stupid. That’s just for starters.

I tend to think both Crowley and Rand had similar, equally misguided, idealistic notions about America and the myth of ‘rugged individualism.’ Crowley wrote glowingly about America and its so-called values, in an underhanded slight, commenting on “the original brand of American freedom—which really was Freedom—contained the precept to leave other people severely alone, and thus assured the possibility of expansion on his own lines to every man” (NC to AL 1.31). Nothing could be further from the truth of the matter in a country that was grounded in building of whole social institutions on top of the pooling blood of the indigenous population.

Rand (1947) was far more wordy on the subject than Crowley, but just as asinine as Crowley:

America is the land of the uncommon man. It is the land where man is free to develop his genius—and to get its just rewards. It is the land where each man tries to develop whatever quality he may possess and to rise to whatever degree he can, great or modest. It is not the land where one glories or is taught to glory in one’s mediocrity. No self-respecting man in America is or thinks of himself as “little,” no matter how poor he may be. That, precisely, is the difference between an American working man and a European serf. (p. 40)

And once again, Rand (1984a) writes:

There have never been any “masses” in America: the poorest American is an individual and, subconsciously, an individualist. Marxism, which has conquered our universities, is a dismal failure as far as the people are concerned: Americans cannot be sold on any sort of class war; American workers do not see themselves as a “proletariat,” but are among the proudest of property owners. It is professors and businessmen who advocate cooperation with Soviet Russia—American labor unions do not. (p. 212)

Whatever one may think of Marxism, and the current boogieman of the political Right, her statements are clear about the position of the individual over the collective, that wealth or the lack thereof are not indicators of success or failure in regard to the value of the individual as many of her detractors claim otherwise. (Though note her denigration of “businessmen” here, for those who think she’s all about business and fuck the individual.)

Crowley echos this stark individualism most directly when he states, “The family, the clan, the state count for nothing; the Individual is the Autarch” (Crowley, 1991b, p. 303).

Of course, this doesn’t really matter to those who feel that Crowley (and/or Rand) went overboard with this radical individualistic perspective. (I am one of those, I should add here, for reasons I’ll discuss another time.) I merely want to point out a foundational similarity to the position that is held by both Crowley and Rand about the centrality of the individual. Thelema does have this centrality as well, but it’s not as radical or as fundamental as some of our own extremists would have us believe. Much like taking Rand through a critical approach, we have to ensure that we approach Crowley in the same manner.

I think it’s interesting that when you start to dig deeper into Rand’s philosophical linguistics, you find her statements like this one concerning the hero of the The Fountainhead. Rand (1997) writes

The idea of individualism is not new, but nobody had defined a consistent and specific way to live by it in practice. It is in their statements on morality that the individualist thinkers have floundered and lost their case. They had nothing better to offer than vulgar selfishness which consisted of sacrificing others to self. When I realized that that was only another form of collectivism—of living through others by ruling them—I had the key to The Fountainhead and to the character of Howard Roark.

My emphasis over the last couple of decades has been the connection between Crowley and Rand on the level of ethics, to understand how selfishness fit into Thelema as defined by both Crowley and Rand. What Motta calls the “social aspect” of Thelema, I believe, is the intersection between individual ethics and communal politics. Where does society fit in with the individual? How does the individual act in deference to society? The answer is the difference between altruism and selfishness (as defined by Rand and Crowley, separately but in surprising congruency with each other).

I’ve already pointed out how Rand defined altruism.

Crowley defines altruism as “the yielding of the self to external impressions” (which is very much a near-mystical or even psychological definition in line with Rand’s) and “a direct assertion of duality, which is division, restriction, sin, in its vilest form” with reference to “this folly against self” in Liber AL 2.22. In the same reference, he calls altruism “hideously corrupting both to the [puritanical] hypocrite and to his victim.” Crowley (1991a) addresses this verse again, twice, when he says, “the idea is to dismiss, curtly and rudely, the entire body of doctrine which insists on altruism as a condition of spiritual progress” (p. 274); and then again, “So ‘… It is a lie, this folly against self. …’ only means, ‘To hell with sentimental altruism, with false modesty, with all those most insidious fiends, the sense of guilt, of shame—in a word, the ‘inferiority complex’ or something very like it’” (p. 278).

Granted, I think Crowley was tainted by his experience with a radical branch of Christianity, but he stands on the same ground as Rand’s own version of radial anti-Communism that she defined as capitalism. Both go overboard when it comes to altruism, needlessly redefining it as some kind of maladaptive human trait.

But I prefer to see altruism defined as that which occurs “in all interactions in which some individuals benefit others at cost to themselves. […] It may be indirect or direct, involuntary or voluntary, and one-way or reciprocal, and costs may be paid by acts or in other ways” (Darlington, 1972, p. 385). This provides no moral connotation to the concept of altruism and understands it from the view of an evolutionary imperative. Because we have no moral foundation for the term, it could go either way. In an evolutionary sense, altruism enhances the chances of survival of adaptation. In a social sense, while it is still a survival trait at a group/kinship level, it has the potential to swing the other direction and be predatory. This is what both Crowley and Rand were attempting to warn against.

What we find in the pathological approach to altruism is this concept by Rand called the sanction of the victim, “the willingness of the good to suffer at the hands of the evil, to accept the role of sacrificial victim” (Peikoff, 1976). I think that might be a bit extreme, language-wise, but I see the point and I see this in action all around us. For Crowley, the “idea of self-sacrifice is a moral cancer” (NC to AL 1.42). He’s not talking about being nice to your neighbor over the fence or taking dinner over to a bedridden friend. He’s specifically talking about this idea of another having a lease, a hold, a lien on someone’s life and liberty.

Crowley (1996) even talks about this in one of is most often quoted diary entries (about being “mislead by the enthusiasm of an illumination,” but it very much remains appropriate in this current context)

if he should find apparent conflict between his spiritual duty and his duty to honour, it is almost sure evidence that a trap is being laid for him and he should unhesitatingly stick to the course which ordinary decency indicates … I wish to say definitely, once and for all, that people who do not understand and accept this position have utterly failed to grasp the fundamental principles of the Law of Thelema.” (p. 21)

Duty of honor. That may include “being nice to your neighbor.” That may include saving the drowning child. That may be feeding the homeless. But in all things we come back to several important injunctions from the Book of the Law: “thou hast no right but to do thy will” (AL 1.42) and “There is no law beyond Do what thou wilt” (AL 3.60), for example.

Your will is central to all decisions to be made—and if you’re being a jackass, well, I would submit that you have stepped outside the bounds of “ordinary decency.” You have been led astray to think that any one person may impose their will upon you. Conversely, though, you have no right upon another. This is the point that both Crowley and Rand make—though I think Rand makes it far more succinctly.

I said that I’d come back to the challenge I’ve offered for decades now. I’ve only ever provided the response in public once. I’ll do so again here for you.

Rand writes, in Atlas Shrugged, the oath of John Galt’s utopian Atlantis: “I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine” (Rand, 1995, p. 670-671). It is the single sentence that sums up the whole of the novel. It is really the sentence that sums up the ethics of Thelema as well quite succinctly.

Likewise, the Law of Thelema posits that we are self-contained aggregates of experience that have no right to another’s will, another’s existence, another’s labors. Yet we also find there is a communion, a connection, between all individuals that form the whole ‘company of heaven’ (AL 1.2). This injunction from Rand falls in line with the verses from the Book of the Law that I offered up earlier, but I’ll leave here again: “thou hast no right but to do thy will” (AL 1.42) and “There is no law beyond Do what thou wilt” (AL 3.60).

Rand was not against groups of individuals. She was against collectivism which she defined as “the subjugation of the individual to a group—whether to a race, class or state” (Rand, 1944, p. 88). She bemoaned what she called the view of society as “a super-organism, as some supernatural entity apart from and superior to the sum of its individual members” (Rand & Branden, 1964a, p. 103) and that “a group, as such, has no rights other than the individual rights of its members” (Rand & Brandon, 1964b, p. 129). Crowley vacillated between his desire to run a cult and the individualistic approach to spiritual self-actualization, but he consistently sided on individualism as the priority for every man and every woman. Granted, I also believe that Crowley, via Thelema, was far more balanced when it comes to understanding the agency of the individual and the communion of existence. The closeness, however, of Crowley and Rand in their ethical perspectives cannot be overstated.

I realize I’ve already said this, in so many words, and I promise I’m wrapping this up. It’s a complex topic that could take way more time than I have on it. My goal was to compare merely the bare minimum of an ethical connection between Crowley (via Thelema) and Rand. I think I’ve done that.

Allow me a moment to address what I know is coming: if everyone is selfish per Rand, that they will “do their own thing” and never help others, it will be a dog-eat-dog world of people stepping all over each other.

Will it?

Rand (1998) writes

Do not make the mistake of the ignorant who think that an individualist is a man who says: “I’ll do as I please at everybody else’s expense.”

An individualist is a man who recognizes the inalienable individual rights of man—his own and those of others. An individualist is a man who says: “I will not run anyone’s life—nor let anyone run mine. I will not rule nor be ruled. I will not be a master nor a slave. I will not sacrifice myself to anyone—nor sacrifice anyone to myself.” (p. 84)

Allow me to repeat a third time: “thou hast no right but to do thy will” (AL 1.42) and “There is no law beyond Do what thou wilt” (AL 3.60).

And I’ll close with the original verse that led to this discussion in the first place. I think, now, of all times, it’s relevant to see how it fits: “Beware therefore! Love all, lest perchance is a King concealed! Say you so? Fool! If he be a King, thou canst not hurt him” (AL 2.59).

Let me add a quick postscript about how I feel concerning the rest of Rand’s philosophy.

Frankly, I think her metaphysics are punked. Her epistemology, as much as I can remember it, seems to be okay even if a little shaky in places (I think Peikoff does a better job). In the end, both Crowley (via Thelema) and Rand advocate a metaphysical position of self-determination, an epistemological position of self-exploration, and an ethical position of self-accountability. I don’t believe the natural conclusion for politics is the same with Thelema and Rand—specifically due to the fact that Rand is still dealing with the foundation of a Christian worldview despite her renunciation of it. She can’t avoid it and it taints everything from her metaphysics on up (down?). But Crowley’s politics, such as they are, aren’t much better either.

Love is the law, love under will.

B∴

References

Crowley, A. (1975). The commentaries of AL: Being the Equinox, volume V, no. 1. M. Motta (Ed.). Weiser Books.

Crowley, A. (1991). Chapter XLII: This “Self” introversion. In Magick without tears. New Falcon Publications.

Crowley, A. (1991). Chapter XLVIII: Morals of AL—Hard to accept, and why nevertheless we must concur. In Magick without tears. New Falcon Publications.

Crowley, A. (1996). Magical Diaries of Aleister Crowley : Tunisia 1923. S. Skinner (Ed.). Weiser Books.

Darlington, P. J. (1978). Altruism: Its characteristics and evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 75(1), 385-389. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.75.1.385

Peikoff, L. (1976). The philosophy of Objectivism lecture series, lecture 8. https://courses.aynrand.org/campus-courses/the-philosophy-of-objectivism/

Rand, A. (1944, January). The only path to tomorrow. Reader’s Digest, 88-90.

Rand, A. (1947, November). Screen guide for Americans. Plain Talk, 40.

Rand, A. (1963). For the new intellectual. In For the new intellectual: The philosophy of Ayn Rand. Signet.

Rand, A. (1975). Art and cognition. In The romantic manifesto: A philosophy of literature (2nd ed.). Signet.

Rand, A. (1975). Basic Principles of Literature. In The romantic manifesto: A philosophy of literature (2nd ed.). Signet.

Rand, A. (1984). Don’t let it go. In Philosophy: Who needs it. Ayn Rand Library.

Rand, A. (1984). Faith and force: The destroyers of the modern world. In Philosophy: Who needs it. Ayn Rand Library.

Rand, A. (1995). Atlas shrugged. Signet.

Rand, A. (1997). Letters of Ayn Rand. Plume.

Rand, A., & Branden, N. (1964). Collectivized ‘rights,’. In The virtue of selfishness: A new concept of egoism. Signet.

Rand, A., & Branden, N. (1964). Racism. In The virtue of selfishness: A new concept of egoism. Signet.

Rand, A., Branden, N., Greenspan, A., & Hessen, R. (1967). What is capitalism? In Capitalism: The unknown ideal. New American Library.

Rand, A., & Schwartz, P. (1998). Textbook of Americanism. In The Ayn Rand column: Written for the Los Angeles times. Second Renaissance Press.